Content Warning

Content Warning

Content Warning

Content Warning

Content Warning

Content Warning

Content Warning

Content Warning

Content Warning

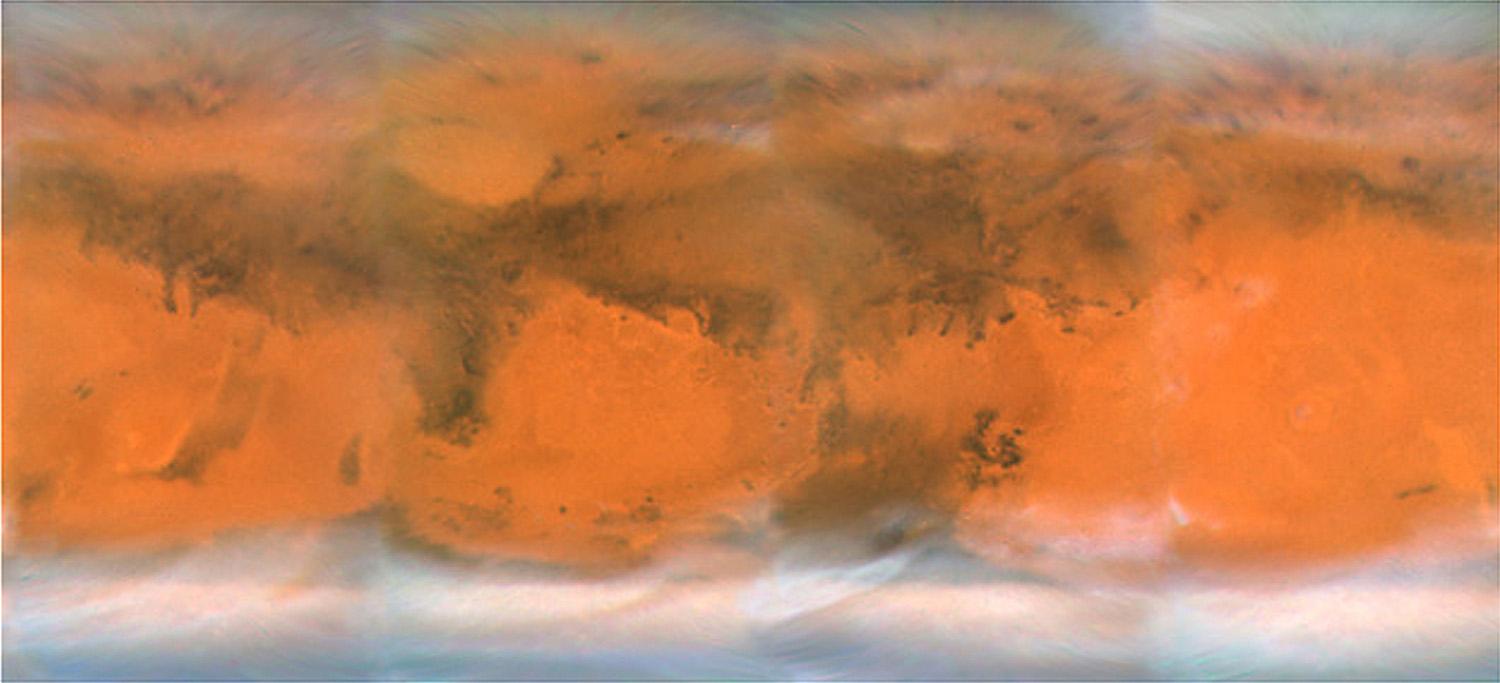

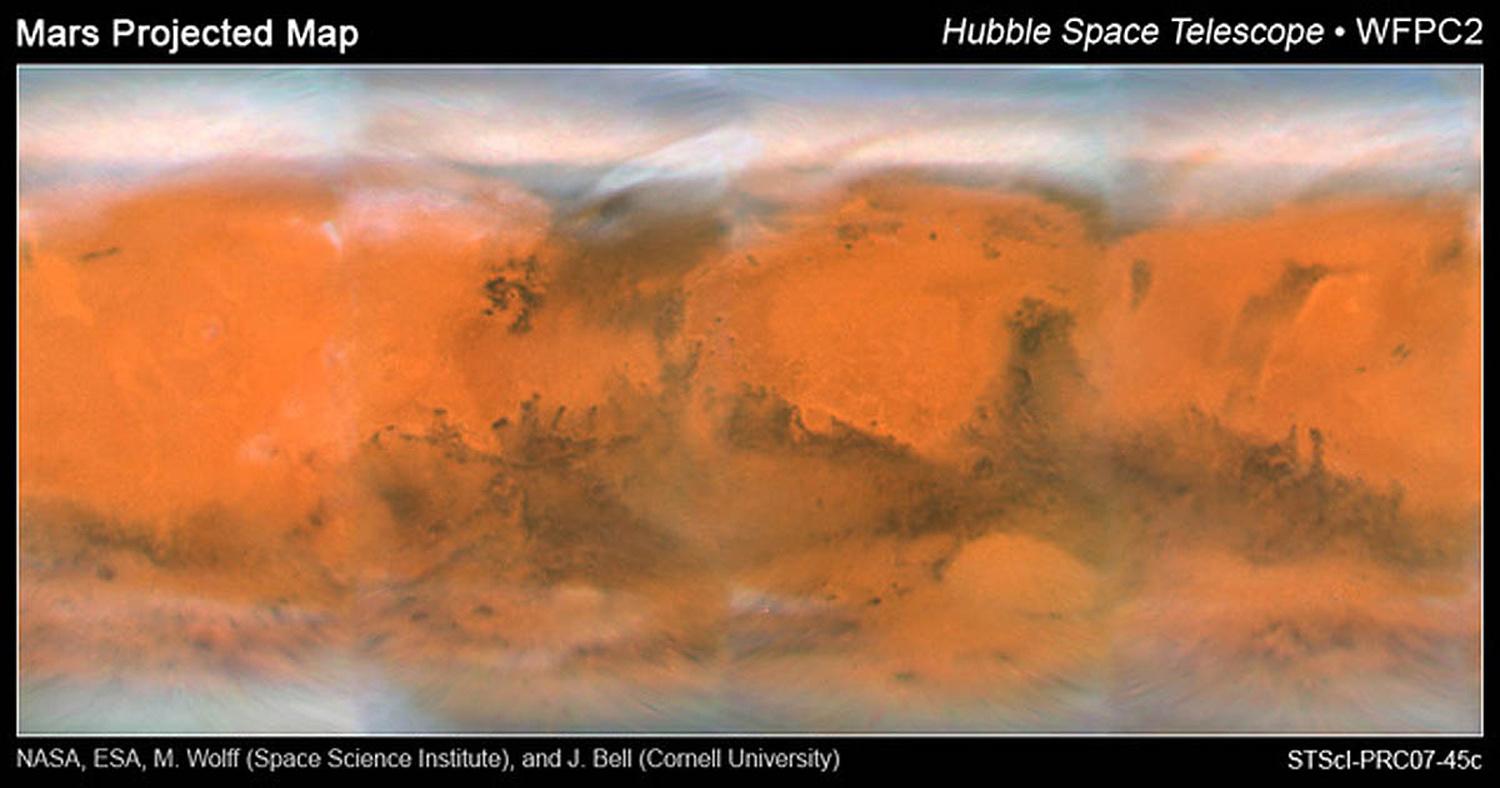

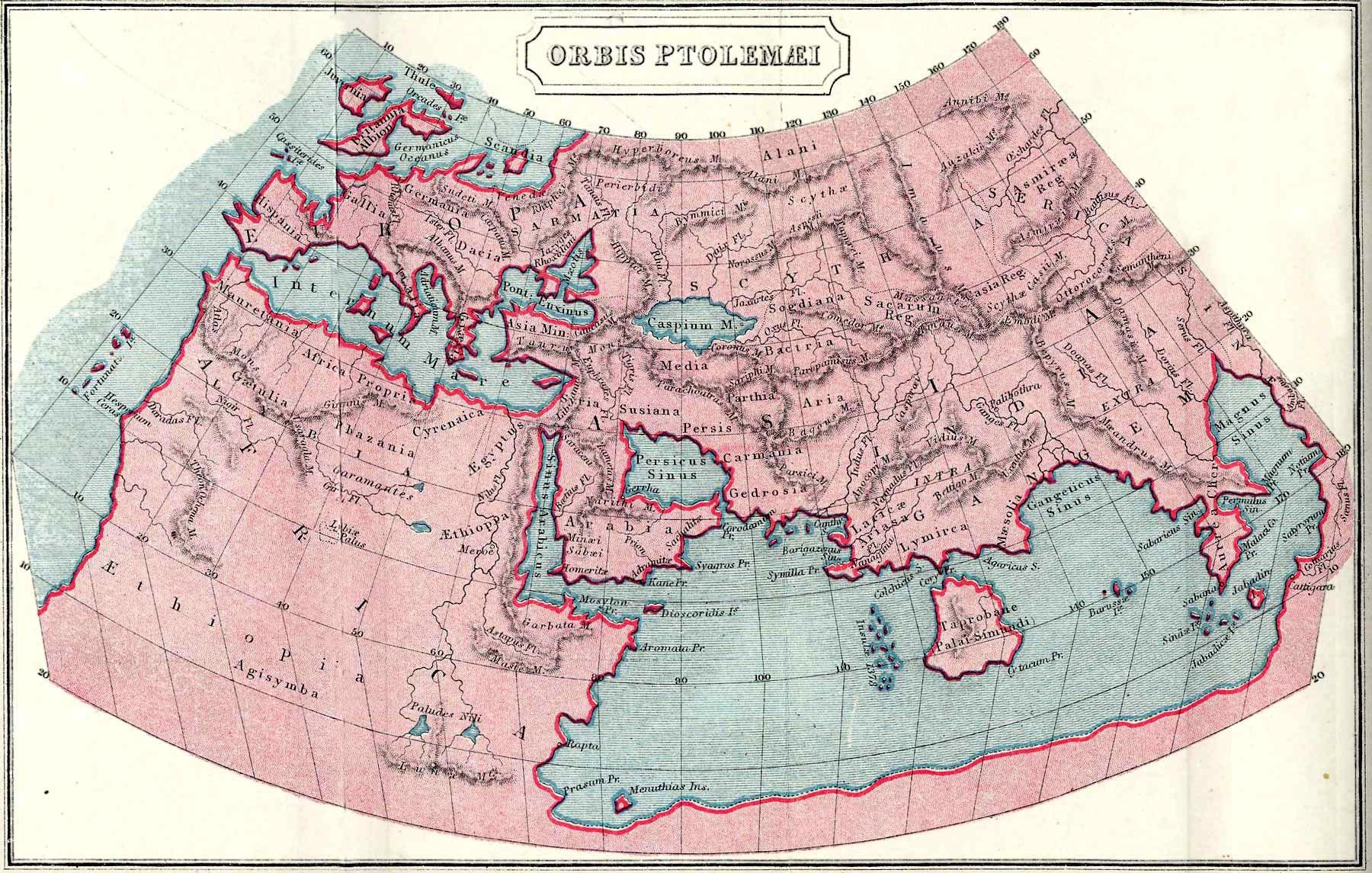

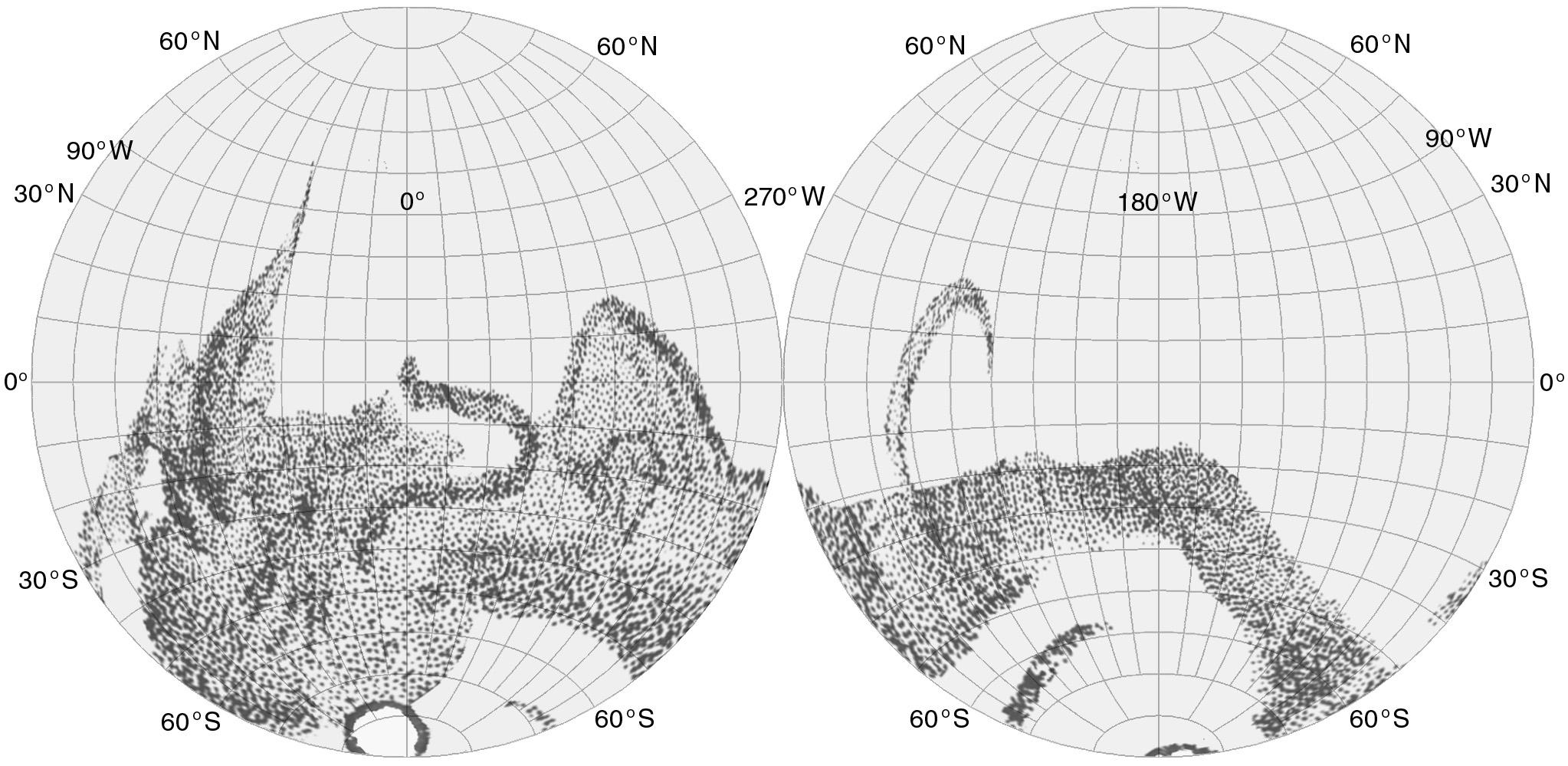

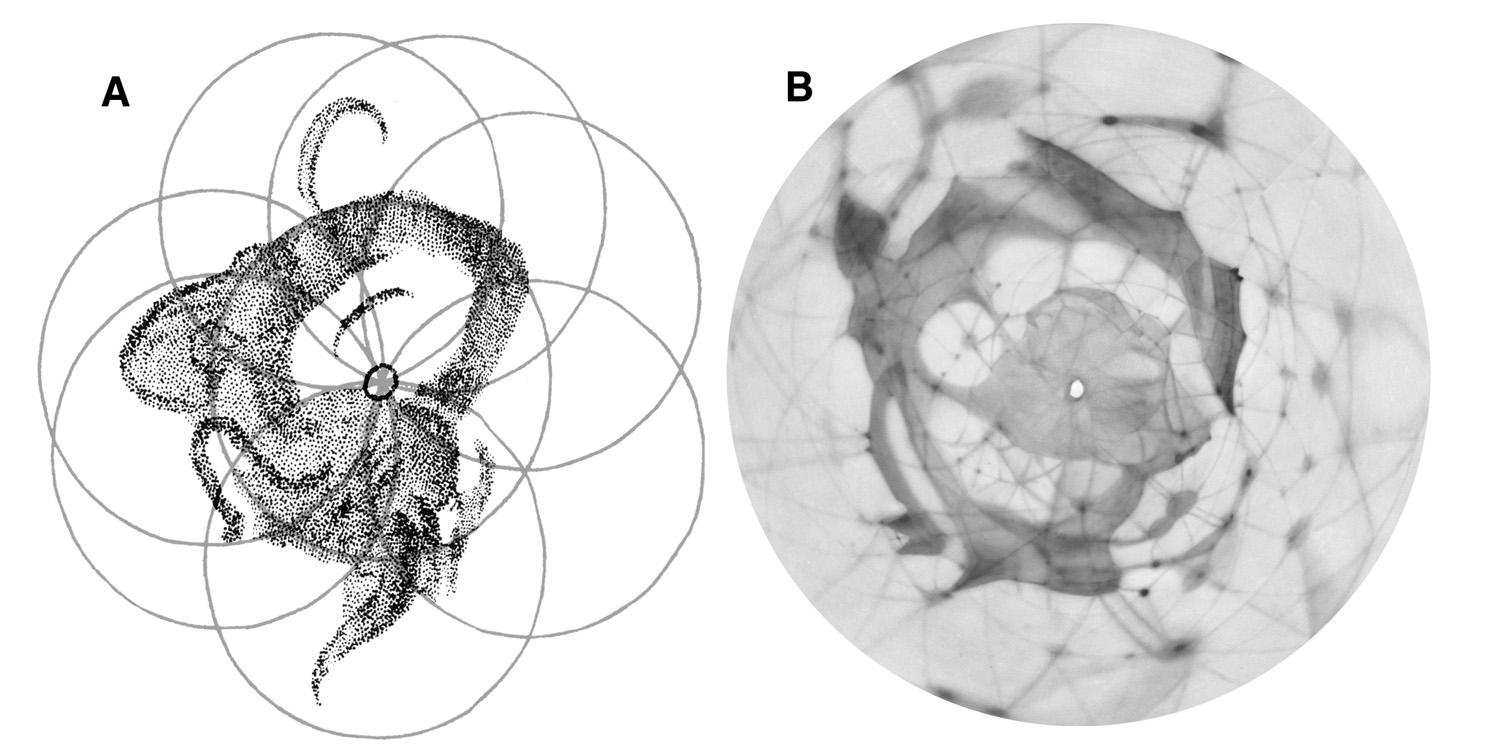

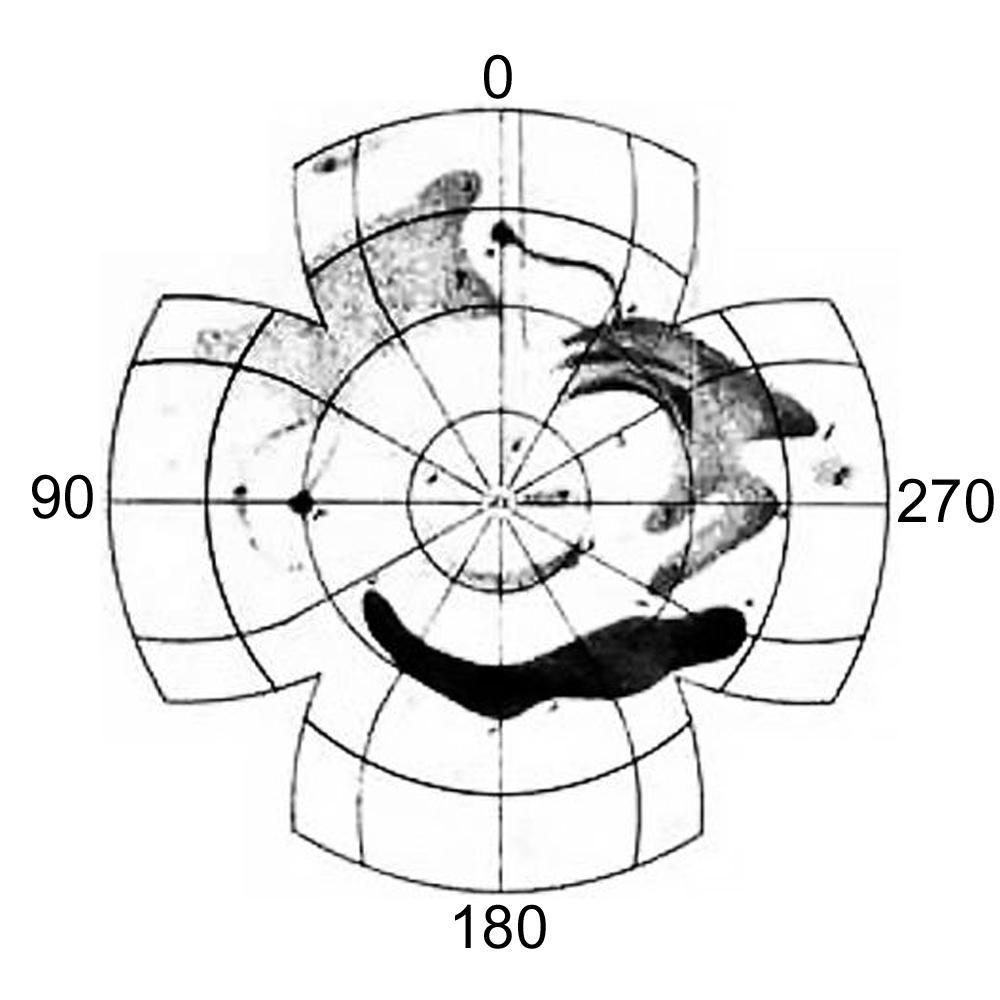

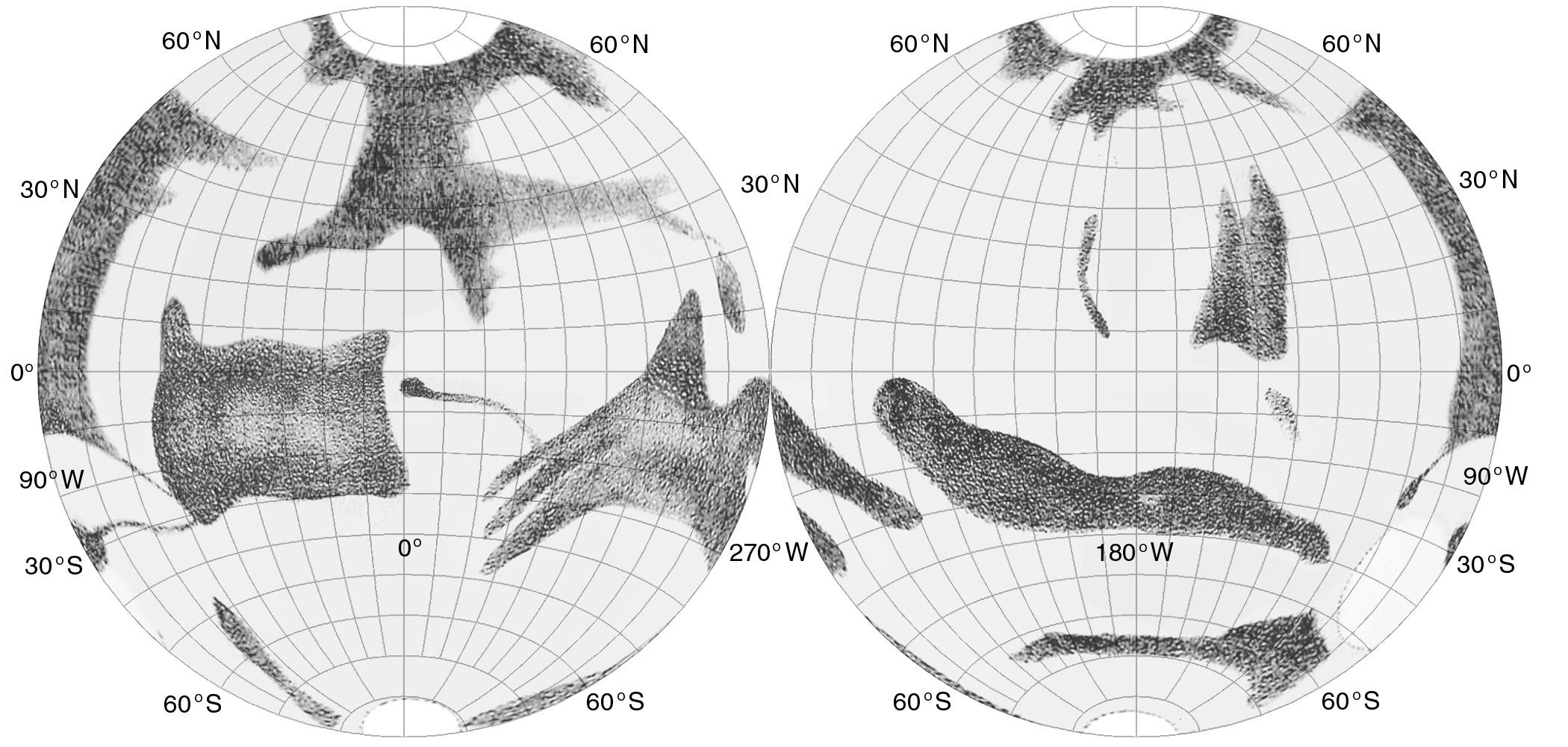

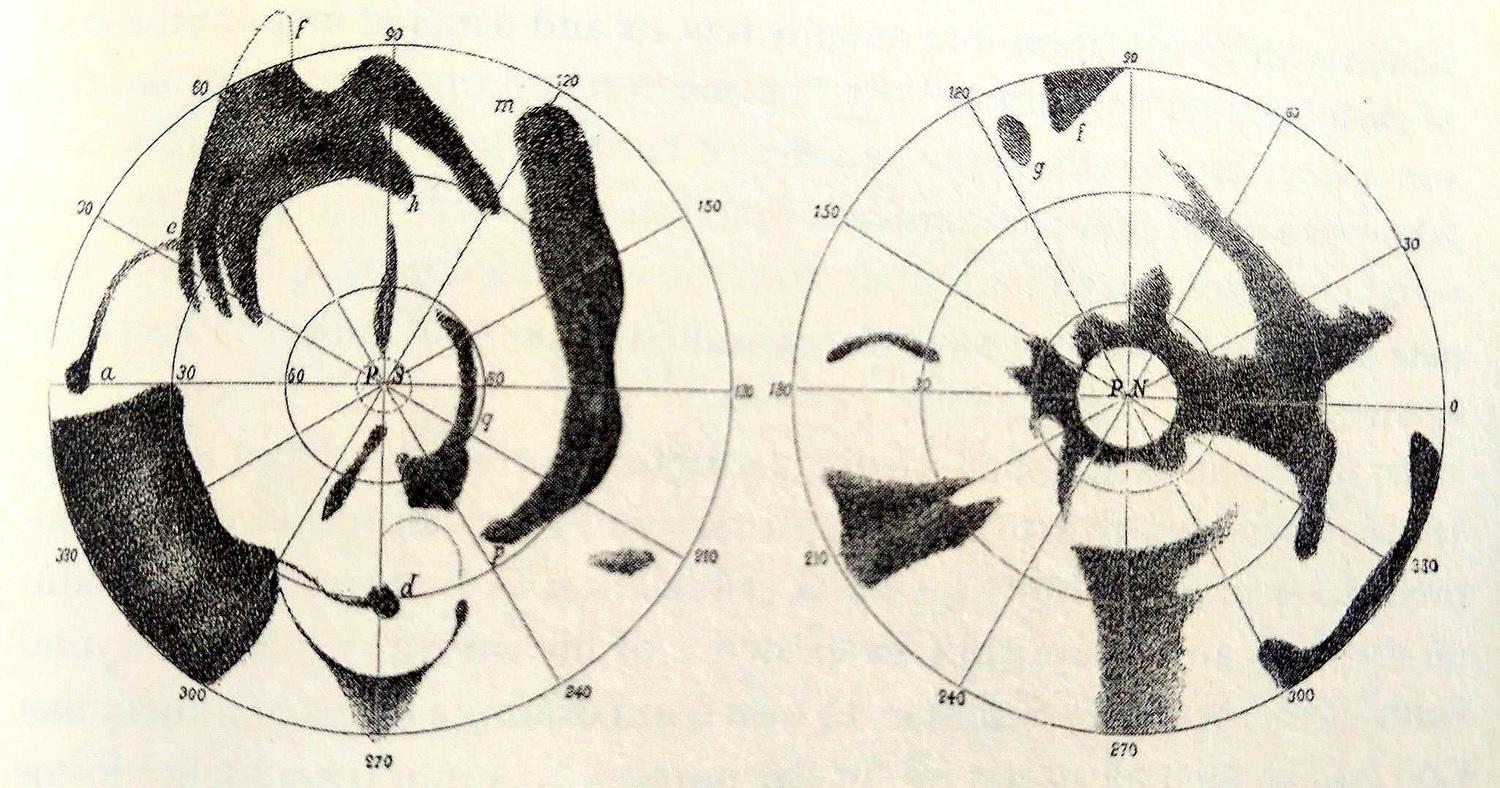

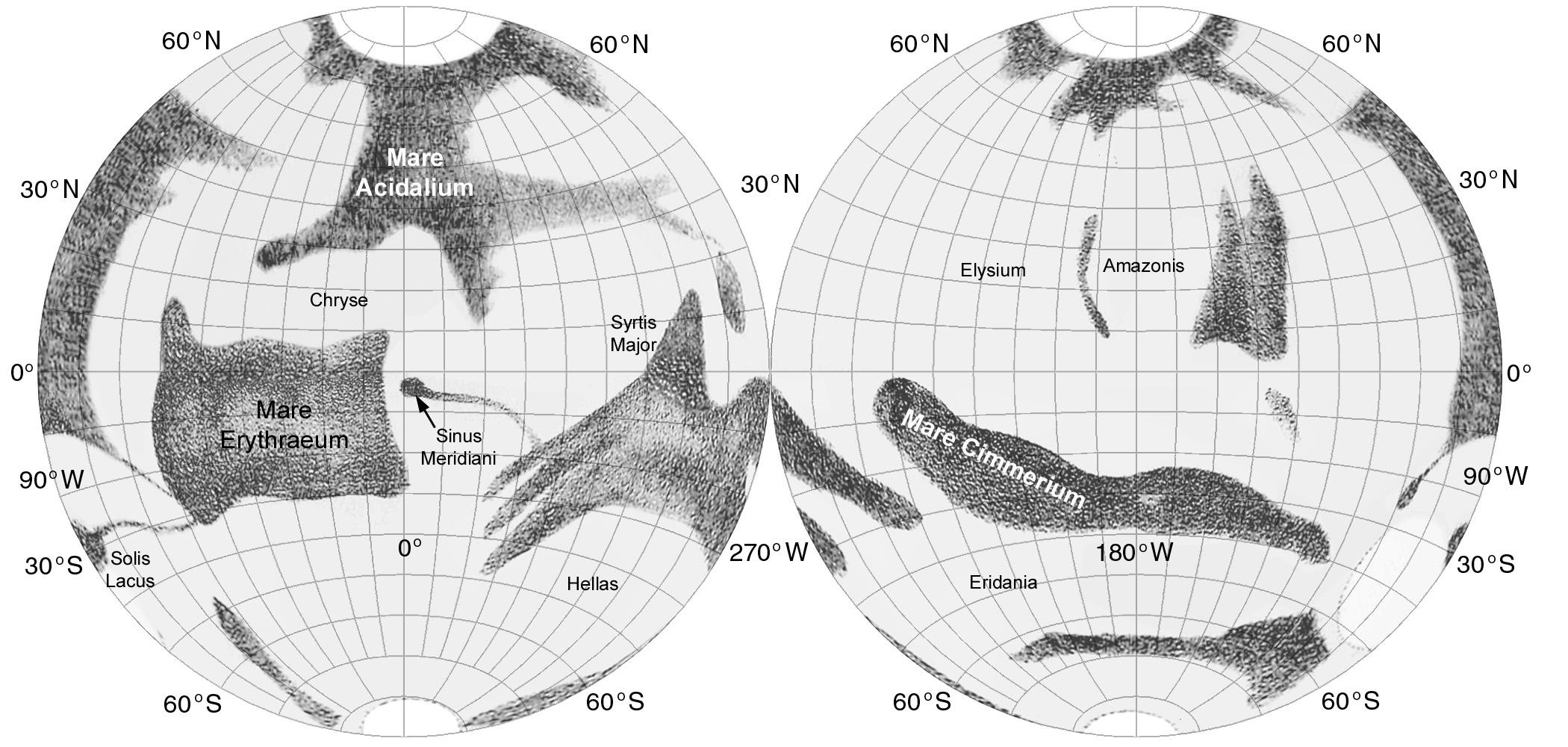

These maps are from my first Mars atlas. I won't show every historic Mars map, just a few interesting ones. #maps #mars

Content Warning

https://asc-planetarynames-data.s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/rhea_comp.pdf

If you want to explore all such solar system names, go here:

https://planetarynames.wr.usgs.gov/

Use the menu bar underneath the banner image to explore names on maps of many worlds. You will notice asteroids are included. But interestingly, for some reason, not comets. I don't know why not. Even Rosetta's amazing comet 67P, which did get names in publications, never got official status for them. #maps #planets